A vast “gene bank” of ancient ceramics has been established at the Imperial Kiln Institute of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province, eastern China. This unique initiative marks the transition from traditional archaeological intuition to scientific, high-tech analysis. Using digital modeling, robotics and extensive databases, Chinese researchers are not only preserving the fragments of the past but also decoding the technological and cultural “codes” of Chinese porcelain dating from the late Tang dynasty (618–907) to the Republic of China (1912–1949).

Jingdezhen’s initiative is a response to the 21st-century challenges of preserving material heritage. Porcelain—one of the most iconic symbols of Chinese civilization—is now undergoing a kind of digital “DNA test.” The main goal is to build a standardized repository of samples and a unified data system that supports scientific authentication, academic research and the revival of traditional craftsmanship.

🏛️ Birth of a Dream: From Intuition to Science

For centuries, the identification and authentication of ceramic artifacts unearthed from kiln sites relied heavily on expert intuition, experience and visual assessment. Although this method laid the foundations of archaeology, it remained subjective and lacked a unified scientific basis.

According to Wen Yanjun, head of the Imperial Kiln Institute, the creation of a ceramic gene bank is something archaeologists once could only dream of. The gene bank has fundamentally transformed the process by providing a standardized sample repository and a unified data system. Now every fragment becomes not just a shard, but a key to an integrated information network. Rows of transparent boxes in elegant grey iron cabinets store thousands of samples, while robots continuously produce new ceramic specimens for research and reconstruction.

Jingdezhen: The Heart of Porcelain Civilization

The city of Jingdezhen is a natural center for the project. Known as China’s ancient porcelain capital, it boasts more than a thousand years of continuous ceramic production. Since the late 1970s, the Ceramic Archaeology Institute of Jingdezhen has uncovered over 20 million artifacts.

Of particular value are the porcelain fragments from the imperial kilns of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1911). Unlike items from private collections, these pieces come with documented archaeological context and rich typological diversity. They form the cornerstone of the authoritative digital database that powers the gene bank.

💡 The Technological Code: How Heritage Is Digitized

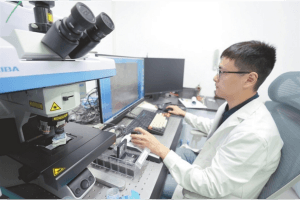

The gene bank is an interdisciplinary project combining archaeology, chemistry, materials science, and information technology. In June 2022, the institute—together with Tsinghua University, the Palace Museum in Beijing, and the Shanghai Institute of Ceramics—launched the creation of standardized reference samples and a knowledge-graph-based database.

The digitization process includes:

• 3D modeling: For representative samples and their reconstructed forms.

• Data integration: Archaeological data, physical attributes, condition reports, and chemical analyses (clay composition, glazes).

• Unified access: A researcher can simply scan a QR code on a shard to access complete information. To date, more than 3,000 selected samples have been digitized, producing nearly 1.2 million data points — making the database one of the most authoritative ceramic data repositories in the world.

Practical Applications and Case Studies

As Wen emphasizes, “The goal of the gene bank is to use science and technology to decode the knowledge embedded in ancient ceramics and apply it in modern innovation.” The gene bank has already proven valuable in research and authentication.

One notable case involves a Dutch collector who sought identification of a dragon-patterned porcelain plate purchased many years earlier. Despite extensive testing in European laboratories, the plate’s origin remained unclear. Wen’s team selected 17 comparative samples from the gene bank covering the Ming and Qing dynasties. The “porcelain DNA test” conclusively showed that the plate was made in a folk kiln during the late Qing period.

In cooperation with Peking University, gene bank data enabled in-depth studies of blue-and-white porcelain from the Yuan and Qing dynasties. Sub-micron analysis confirmed the coexistence of imported and local raw materials from the Xuande period onward—an important breakthrough for understanding historical trade routes and technologies.

Impact on the Economy and Global Culture

The gene bank holds strategic value for both history and the modern economy.

First, it enables the revival of craftsmanship. Using gene bank data, researchers have precisely recreated iconic artifacts such as the blue-and-white loop-handled cup from the Yongle period. Detailed information on form, glaze chemistry and inscription styles allows reconstructions to be scientifically accurate.

Second, it supports the development of creative industries. The institute publishes structural and chemical data on artifacts (such as the duck-shaped incense burner “Daktor Sui”). These data underpin a new wave of innovative cultural products successfully entering the market.

As Wen concludes:

“By opening the gene bank to the public, we encourage broader participation and support the creative transformation of traditional culture.”

The Jingdezhen Gene Bank project is a vivid example of how cutting-edge digital technologies can be integrated into the humanities. It transforms Chinese archaeology, strengthens China’s global leadership in cultural heritage preservation, and breathes new life into the timeless art of Chinese porcelain.

ORIENT